Hakan Şükür (46), who is now selling coffee in a bakery in Palo Alto, California, despite the fact that he is one of Turkey’s most famous athletes, told John Branch of The New York Times (NYT) in an interview published on Thursday that “There are thousands and thousands of people living in this situation. … I wouldn’t be so selfish to just defend my own rights, to just keep my benefits over everything else. I would lose all respect to myself.”

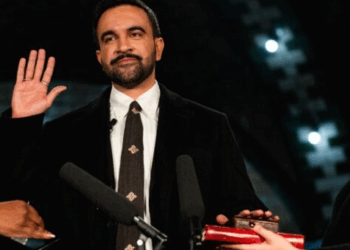

The NYT introduced Şükür to its readers as Turkey’s most celebrated soccer player, a World Cup hero and a veteran of several of Europe’s top leagues. “He parlayed his fame into a political career and was elected to Turkey’s Parliament. Even with his sideburns tinged gray, his face and name are instantly recognized back home,” wrote Branch.

Talking about Turkey during his first interview since he left Turkey in 2015, Şükür told the NYT: “It’s my country; I love my people, even though their ideas about me are distorted by controlled media. … Maybe in the future we will go there and visit.”

Reminding that “more than 60,000 people, journalists, academics, political opponents or anyone brave or foolish enough to spout an opposing viewpoint, have been jailed” since a coup attempt in Turkey on July 15, 2016, The New York Times wrote that “[Turkish President Recep Tayyip] Erdogan has taken strong-armed control of the military, the courts, the media and, most recently, the internet.”

“Şükür, his wife and their three children were already out of the country by the time of the coup attempt, sensing the deteriorating state of affairs there. But Şükür’s political ties, fame and wealth made him a target of Erdogan’s widespread distrust and accusations,” Branch wrote and added that “Şükür had warrants out for his arrest, and his father was jailed for nearly a year. Şükür, as famous as anyone in Turkey, said his houses, businesses and bank accounts there had all been seized by Erdogan’s government.”

The New York Times reminded that “While it had been reported in Turkey that Şükür was hiding in the United States, it was only last fall that Turkish state-run media reported his precise whereabouts, publishing photographs and a video of Şükür surreptitiously recorded in Palo Alto.”

Despite his friends in Turkey secretly telling him that he could return and have it all back if only he would be publicly supportive of Erdoğan and the Turkish government, Şükür said: “I would have lived a very good life and become a minister if I had played the game accordingly, if I did what they say. … But now I am selling coffee. … There is not always darkness. … I believe one day the light will return. Darkness doesn’t last forever.”

Stating that Şükür was also a follower of US-based Turkish Muslim scholar Fethullah Gülen, The New York Times told the story of how Şükür parted ways with Erdoğan’s ruling party after tension erupted between the Erdoğan’s regime and the Gülen movement.

“Tensions and hostilities quaked through Turkey as Erdogan clamped down on the areas of society he saw as threats, including the news media. Opponents were silenced and increasingly jailed. Şükür, with his popularity and influence, was among the most prominent of the new enemies,” wrote Branch.

“After I left the Parliament, I started to face administrative issues with my businesses there,” Şükür said. “Whatever I wanted to do, there was some problems and issues. I thought that maybe I will just take some time off, since the work was limited. Maybe I’ll get peace of mind and see my opportunities.” So, in the fall of 2015, Şükür came to Palo Alto.

According to the report, Şükür spent a month in California while Turkey’s upheaval worsened. He bought a share of a bakery and cafe that a friend was opening in 2016, secured an investor’s visa and told his wife, Beyda, and their children (two daughters, now 18 and 16, and a son, age 12) to come.

“I want them to be free, to be independent people,” Şükür said. “Being in Turkey, the children of a famous person, maybe they are treated differently. I wanted my kids to go to other countries, learn different cultures, meet different people and stand up as individuals. That was one reason we came here. And once things got worse in Turkey, we thought it was a good time.”

“Şükür knows he is vastly luckier than most people in Turkey who are unable or unwilling to speak their minds, or who have been imprisoned for doing so. Still, agreeing to be interviewed carried some anxiety, knowing his words will be parsed in Turkey and may be used against family and friends there. Şükür is mindful of his security in the United States but not overly so. He moves freely but preferred not to meet at home. He asked that the names of his children not be used in this article,” according to the NYT.

Şükür told the Times that recently he had a conversation with a friend, a Turkish television personality, and they agreed on how bad things were in Turkey. Then he saw an interview the friend gave to a Turkish newspaper, complimenting the government. “I just talked to him the other night,” Şükür said. “He said, ‘What else can we say here?’ He even said, ‘If you keep silent, maybe you can return and they will not do anything’.”

That is not possible, Şükür said. “There are thousands and thousands of people living in this situation,” told to NYT. “I wouldn’t be so selfish to just defend my own rights, to just keep my benefits over everything else. I would lose all respect to myself.”

According to the report Şükür and his family regularly speak to his parents through FaceTime. His father, 77, is out of jail but fighting cancer. His mother thanks God for the people who invented her phone so that she can see her son’s face.

“Last Friday my father says to my son, ‘I miss you,’ ‘I want to hug you.’ And then my son started to cry, and my father was crying, and we were all crying. I know there are millions of people living in these conditions in the US for a very long time, unable to go home and hug their loved ones.”

Turkey survived a military coup attempt July 15, 2016 that killed 249 people. Immediately after the putsch, the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government along with President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan also pinned the blame on the Gülen movement.

Fethullah Gülen, who inspired the movement, strongly denied having any role in the failed coup and called for an international investigation into it, but President Erdoğan — calling the coup attempt “a gift from God” — and the government initiated a widespread purge aimed at cleansing sympathizers of the movement from within state institutions, dehumanizing its popular figures and putting them in custody.

Turkey has suspended or dismissed more than 150,000 judges, teachers, police and civil servants since July 15. On December 13, 2017 the Justice Ministry announced that 169,013 people have been the subject of legal proceedings on coup charges since the failed coup.

Turkish Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu announced on April 18, 2018 that the Turkish government had jailed 77,081 people between July 15, 2016 and April 11, 2018 over alleged links to the Gülen movement.

(Stockholm Center for Freedom [SCF])